Now Reading: The Slow Fade of a Visionary: What’s Going Wrong with Sonam Wangchuk’s Journey

-

01

The Slow Fade of a Visionary: What’s Going Wrong with Sonam Wangchuk’s Journey

The Slow Fade of a Visionary: What’s Going Wrong with Sonam Wangchuk’s Journey

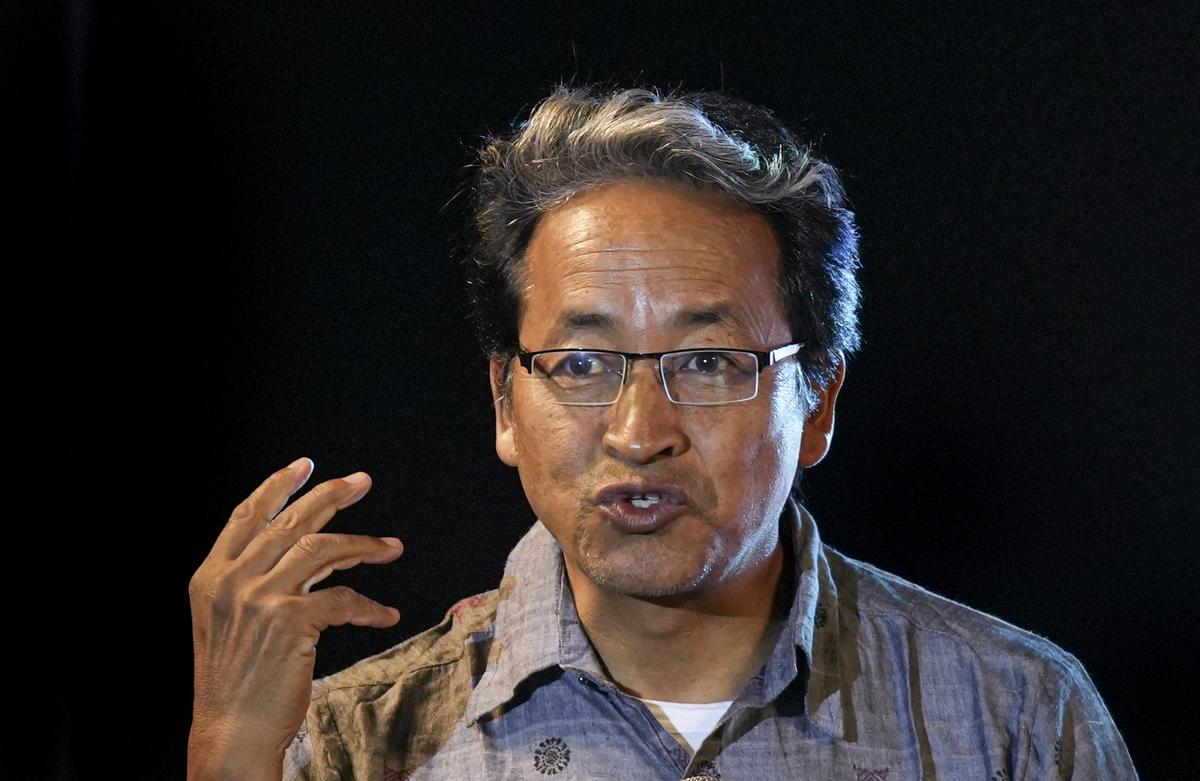

In recent years, Sonam Wangchuk—once admired nationwide as an innovator, educator, and the inspiration behind 3 Idiots’ Phunsukh Wangdu—seems to be drifting from his original promise. From environmental champion to polarising political figure, his career trajectory is raising questions. What led to this shift, and what does it say about activism, public expectation, and identity in India today?

From Innovator to Political Activist

Wangchuk’s early years were defined by bold experiments—in education, architecture, climate resilience. His work in Ladakh with SECMOL and sustainable design earned him acclaim across India. He stood as proof that local solutions could gain global respect.

But over time, his role morphed. He began speaking more about Ladakh’s governance, autonomy, and identity. His protests around Sixth Schedule inclusion and statehood reflect a shift from purely developmental work to political confrontation.

Rising Credibility Questions

With recognition came scrutiny. Critics argue that his evolving persona sows confusion: Was he an educator first, or a regional political voice? Some feel his activism now carries more ideology than pragmatism, making his messages harder to decode even for supporters.

Another issue is institutional pushback. His NGO lost its FCRA licence, and authorities have increasingly framed his work as subject to legal review. When a nonprofit’s key funding is threatened, the capacity to effect change is undermined.

The Pressure of Iconhood

Expectations play a role too. When someone becomes symbolic—“the real-life Phunsukh Wangdu”—every move draws amplified glare. Mistakes or contradictions get magnified. In cities beyond the metros, where people revere success stories, any perceived backslide becomes a cautionary tale.

Additionally, balancing vision and execution is hard. Grand ideas need reliable systems. Critics say some of his ambitious projects run short on sustainability, follow-up, or scale.

What the Shift Reflects

Wangchuk’s journey mirrors a larger tension in Indian civil society. Activists often start with technical or social work, then discover political dimensions in structural issues. But the transition is complex—aligning grassroots credibility with larger narrative demands is not easy.

In states and union territories where identity, resource access, and autonomy are contested, his path shows the challenge: staying rooted while pushing for systemic change.

Looking Ahead

If Wangchuk wants to rebuild clarity, he may need to recalibrate: reconnect with grassroots methods, delegate more public roles, and frame political arguments with development backing. Transparency about intent will matter more now than ever.

For citizens in Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns following his arc, his rise and struggle underscore one lesson: vision alone isn’t enough—you need structural grounding, clear messaging, and strategy to stay relevant in India’s shifting political-social landscape.

In short, Sonam Wangchuk’s journey is at a turning point—not an end, but a redefinition. How he adapts could determine whether he remains an inspiring innovator, or becomes another polarising figure divided between hope and controversy.